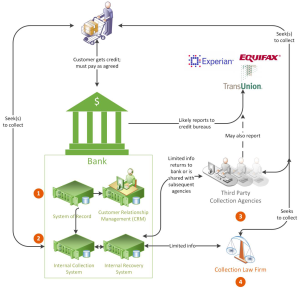

Figure 1 – Data Flows While Debt Is Owned by Creditor– At point (1) the information regarding the consumer and her account is maintained in two systems at the bank, the system of record (which contains transaction information) and the customer relationship management (CRM) system, which contains notes on the customer’s interactions with customer service. As shown in (2), sometime after 30+ days of delinquency, banks will typically move the account to their internal collection system, and perhaps after further delinquency, to their internal recovery system. These may be different departments that have different strategies for “working” the account. At some point, one or more third party collection agencies may be used, as in (3). Finally, some creditors choose to sue on their own delinquent accounts and in those cases hire a collections law firm, as in (4).

Data flows once debt is purchased: Fn. 3

Figure 1 – Data Flows While Debt Is Owned by Creditor– At point (1) the information regarding the consumer and her account is maintained in two systems at the bank, the system of record (which contains transaction information) and the customer relationship management (CRM) system, which contains notes on the customer’s interactions with customer service. As shown in (2), sometime after 30+ days of delinquency, banks will typically move the account to their internal collection system, and perhaps after further delinquency, to their internal recovery system. These may be different departments that have different strategies for “working” the account. At some point, one or more third party collection agencies may be used, as in (3). Finally, some creditors choose to sue on their own delinquent accounts and in those cases hire a collections law firm, as in (4).

Data flows once debt is purchased: Fn. 3

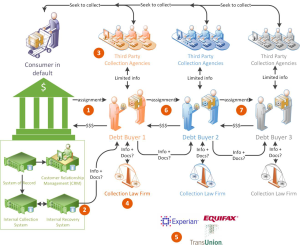

Figure 2 – Data flows once debt is purchased. A debt purchase is an assignment of rights under the original contract (e.g., credit card) between the consumer and the bank. At point (1), the bank assigns the first debt buyer the right to collect on a pool of accounts, for which the debt buyer pays money. Information about the accounts, typically in the form of an Excel spreadsheet is given to the debt buyer as in (2). This diagram does not include the situation in which documentation is not sold with the debt and instead is requested later by the first or a subsequent debt buyer. Sometimes documentation evidencing the contract and debt between the consumer and the bank (e.g., credit card statements, agreement) is also shared. The debt buyer will typically hire a third party debt collection agency, as in (3) to collect from the consumer. It may also seek to collect directly from the consumer (not shown). The first debt buyer (or one of its third party collectors) may report to the credit reporting agencies in (5). At some point, a collection law firm may get involved, (4), whether it is to act as a collector or to initiate a lawsuit in state court. The documentation provided to the law firm may consist of only information about the account or perhaps also documents, including affidavits from the debt buyer or original creditor. At some point, the consumer’s obligation may be repackaged and sold to another debt buyer, as in (6). This may happen even after a judgment has been entered against a consumer. The same cycle will repeat again in very much the same way for any subsequent buyer.

From that point, the article turned to examine the terms of eight-four (84) consumer debt sale and purchase agreements to debt buyers, which the author recognizes is a small sample, largely limited by the reticence of debt buyers to disclose these terms, this article identifies three common types of representations that go to material elements of the purchase:

(1) The seller has unencumbered title to the accounts: 82% of the contracts included affirmative representations that the seller of the debt held unencumbered title to the account.

(2) Previous compliance with the relevant consumer laws: Approximately 25% of the contracts either implicitly or explicitly disclaimed compliance with some or all consumer laws.

(3) Accuracy and completeness of the information: Over one-third of the contracts examined expressly disclaim any warranty as to accuracy, completeness, enforceability or validity of any of the accounts being sold.

Regarding information and documentation concerning debts being purchased this article reveals how details for legally collecting a debt is often missing. Relying on the FTC Debt Buyer Report Fn. 4 this article notes that most accounts sold include information regarding :

(1) name, street address, and social security of the debtor (found in 98% of accounts);

(2) creditor’s account number (found in 100% of accounts);

(3) outstanding balance (found in 100% of accounts);

(4) date the debtor opened the account (found in 97% of accounts);

(5) date the debtor made his or her last payment (found in 90% of accounts);

(6) date the original creditor charged-off the debt (found in 83% of accounts);

(7) amount the debtor owed at charge-off (found in 72% of accounts); and

(8) debtor’s home phone number (found in 70% of accounts).

Many accounts were sold, nonetheless, without some critical information—in particular, the

(1) principal amount (missing from 89% of accounts);

(2) finance charges and fees (missing from 63% of accounts);

(3) interest rate charged on the account (missing from 70% of accounts);

(4) date of first default (missing from 65% of accounts); and

(5) name of the original creditor (missing from 54% of accounts).

When it came to documentation of the debts, called “media” in the debt buyer industry, on 6-12% of accounts included anything at the time of sale. And while documentation was sometimes available upon request, obtaining such was often neither feasible nor possible because:

(1) The purchase and sale contracts between original creditors and debt buyers may preclude some or all media from being transferred or set a prohibitive cost to the debt buyer;

(2) A debt buyer may not, depending on where in the “assignment chain” the debt is, have the right to obtain media from the original creditor or may have to send a request back through each previous debt buyer in the assignment chain; and

(3) The media may have been destroyed or otherwise cannot be retrieved.

These pieces of information and documentation can be vitally important for consumer in determining statutes of limitations, credit reporting periods, an itemization of principal, interest, and fees, and standing under the assignment chain to collect a debt. As the author writes, “[w]ithout documentary evidence, all a debt buyer can do is create an affidavit that quotes the amount on the spreadsheet.” Unmentioned by the article is that many of the most commonly missing items are specifically required in a Proof of Claim filed in a bankruptcy case by Rule 3001(c)(3), making it reasonable to question how reliable such Proofs of Claim can be. `

For a copy of the paper, please see:

Dirty Debts Sold Dirt Cheap

Foot Notes:

Fn. 1: For a companion piece of reading that brings more color to understanding the frequently wild and shady world of debt buyers, read Jake Halpern’s Bad Paper: Chasing Debt from Wall Street to the Underworld available at http://tinyurl.com/ms8zbxf

Fn. 2: John Tonetti, Collections Program Manager, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Presentation at FTC/CFPB Life of a Debt Conference: How Information Flows Throughout the Collection Process (June 6, 2013) (transcript available at: http://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/videos/life-debt-data-integritydebt-

collection-part-1/130606debtcollection1.pdf).

Fn. 3: Jiménez, Dalié, Dirty Debts Sold Dirt Cheap (November 19, 2014). Harvard Journal on Legislation, Vol. 52 (Winter 2014). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2250784 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2250784

Fn. 4: FED. TRADE COMM’N, THE STRUCTURE AND PRACTICES OF THE DEBT BUYING INDUSTRY 23 (2013) [hereinafter FTC DEBT BUYER REPORT], available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/2013/01/debtbuyingreport.pdf, archived at http://perma.cc/XSN6-XXSD. The FTC examined data from The FTC examined data for over five million consumer credit accounts for this report.

Figure 2 – Data flows once debt is purchased. A debt purchase is an assignment of rights under the original contract (e.g., credit card) between the consumer and the bank. At point (1), the bank assigns the first debt buyer the right to collect on a pool of accounts, for which the debt buyer pays money. Information about the accounts, typically in the form of an Excel spreadsheet is given to the debt buyer as in (2). This diagram does not include the situation in which documentation is not sold with the debt and instead is requested later by the first or a subsequent debt buyer. Sometimes documentation evidencing the contract and debt between the consumer and the bank (e.g., credit card statements, agreement) is also shared. The debt buyer will typically hire a third party debt collection agency, as in (3) to collect from the consumer. It may also seek to collect directly from the consumer (not shown). The first debt buyer (or one of its third party collectors) may report to the credit reporting agencies in (5). At some point, a collection law firm may get involved, (4), whether it is to act as a collector or to initiate a lawsuit in state court. The documentation provided to the law firm may consist of only information about the account or perhaps also documents, including affidavits from the debt buyer or original creditor. At some point, the consumer’s obligation may be repackaged and sold to another debt buyer, as in (6). This may happen even after a judgment has been entered against a consumer. The same cycle will repeat again in very much the same way for any subsequent buyer.

From that point, the article turned to examine the terms of eight-four (84) consumer debt sale and purchase agreements to debt buyers, which the author recognizes is a small sample, largely limited by the reticence of debt buyers to disclose these terms, this article identifies three common types of representations that go to material elements of the purchase:

(1) The seller has unencumbered title to the accounts: 82% of the contracts included affirmative representations that the seller of the debt held unencumbered title to the account.

(2) Previous compliance with the relevant consumer laws: Approximately 25% of the contracts either implicitly or explicitly disclaimed compliance with some or all consumer laws.

(3) Accuracy and completeness of the information: Over one-third of the contracts examined expressly disclaim any warranty as to accuracy, completeness, enforceability or validity of any of the accounts being sold.

Regarding information and documentation concerning debts being purchased this article reveals how details for legally collecting a debt is often missing. Relying on the FTC Debt Buyer Report Fn. 4 this article notes that most accounts sold include information regarding :

(1) name, street address, and social security of the debtor (found in 98% of accounts);

(2) creditor’s account number (found in 100% of accounts);

(3) outstanding balance (found in 100% of accounts);

(4) date the debtor opened the account (found in 97% of accounts);

(5) date the debtor made his or her last payment (found in 90% of accounts);

(6) date the original creditor charged-off the debt (found in 83% of accounts);

(7) amount the debtor owed at charge-off (found in 72% of accounts); and

(8) debtor’s home phone number (found in 70% of accounts).

Many accounts were sold, nonetheless, without some critical information—in particular, the

(1) principal amount (missing from 89% of accounts);

(2) finance charges and fees (missing from 63% of accounts);

(3) interest rate charged on the account (missing from 70% of accounts);

(4) date of first default (missing from 65% of accounts); and

(5) name of the original creditor (missing from 54% of accounts).

When it came to documentation of the debts, called “media” in the debt buyer industry, on 6-12% of accounts included anything at the time of sale. And while documentation was sometimes available upon request, obtaining such was often neither feasible nor possible because:

(1) The purchase and sale contracts between original creditors and debt buyers may preclude some or all media from being transferred or set a prohibitive cost to the debt buyer;

(2) A debt buyer may not, depending on where in the “assignment chain” the debt is, have the right to obtain media from the original creditor or may have to send a request back through each previous debt buyer in the assignment chain; and

(3) The media may have been destroyed or otherwise cannot be retrieved.

These pieces of information and documentation can be vitally important for consumer in determining statutes of limitations, credit reporting periods, an itemization of principal, interest, and fees, and standing under the assignment chain to collect a debt. As the author writes, “[w]ithout documentary evidence, all a debt buyer can do is create an affidavit that quotes the amount on the spreadsheet.” Unmentioned by the article is that many of the most commonly missing items are specifically required in a Proof of Claim filed in a bankruptcy case by Rule 3001(c)(3), making it reasonable to question how reliable such Proofs of Claim can be. `

For a copy of the paper, please see:

Dirty Debts Sold Dirt Cheap

Foot Notes:

Fn. 1: For a companion piece of reading that brings more color to understanding the frequently wild and shady world of debt buyers, read Jake Halpern’s Bad Paper: Chasing Debt from Wall Street to the Underworld available at http://tinyurl.com/ms8zbxf

Fn. 2: John Tonetti, Collections Program Manager, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Presentation at FTC/CFPB Life of a Debt Conference: How Information Flows Throughout the Collection Process (June 6, 2013) (transcript available at: http://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/videos/life-debt-data-integritydebt-

collection-part-1/130606debtcollection1.pdf).

Fn. 3: Jiménez, Dalié, Dirty Debts Sold Dirt Cheap (November 19, 2014). Harvard Journal on Legislation, Vol. 52 (Winter 2014). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2250784 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2250784

Fn. 4: FED. TRADE COMM’N, THE STRUCTURE AND PRACTICES OF THE DEBT BUYING INDUSTRY 23 (2013) [hereinafter FTC DEBT BUYER REPORT], available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/2013/01/debtbuyingreport.pdf, archived at http://perma.cc/XSN6-XXSD. The FTC examined data from The FTC examined data for over five million consumer credit accounts for this report.

Blog comments