Available at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/bankruptcy_research_library/376/

Abstract:

Section 502(j) of title 11 of the United States Code (the "Bankruptcy Code") states that "[a] claim that has been allowed or disallowed may be reconsidered for cause" in a bankruptcy case. 11 U.S.C.S. §502(j). Section 502(j) further states that "a reconsidered claim may be allowed or disallowed according to the equities of the case." Id. There is no definition of "for cause" or "according to the equities of the case," but the courts have generally held that reconsideration ultimately "lies within the discretion of the court." This article will analyze the scenarios under which a bankruptcy court in New York and Delaware may reconsider previously allowed or disallowed claims under Section 502(j). First, the memorandum will discuss the governing law applicable to this issue. Subsequently, the article is divided into two sections; the first will highlight situations in which courts have historically granted motions to reconsider claims, while the second will discuss the rationale adopted by courts that deny reconsideration of claims.

Summary:

This note surveys how bankruptcy courts in New York and Delaware reconsider previously allowed or disallowed claims under § 502(j). That section allows reconsideration of claims “for cause” and adjustment “according to the equities of the case,” without defining either term. The memorandum frames the analysis as a two-step process:

-

Determine whether “cause” exists—often evaluated through Bankruptcy Rules 3008 and 9024, incorporating Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b) and its “excusable neglect” standard.

-

If cause exists, decide whether the equities favor allowance or disallowance.

Courts in both districts generally follow the Pioneer factors for excusable neglect—prejudice to the debtor, length and reason for delay, and good faith—but in the default judgment context may instead apply the Second Circuit’s American Alliance test, which omits the “reason for delay” factor and is more forgiving.

Examples of granted reconsideration include cases where creditors lacked notice of objections, delays were short, and claims were facially meritorious (Bluestem Brands, Enron, Coxeter). Denials typically involve long or unexplained delays, willful inaction, lack of new evidence, or untimely motions under Rule 9024’s one-year limit (Gonzalez, Nations First Capital, JWP Info. Servs., Spiegel, Dana, Palmer, Tender Loving Care).

The article concludes that the decision is highly fact-dependent, grounded in equitable discretion, and guided by the interplay of statutory language and procedural rules.

Commentary:

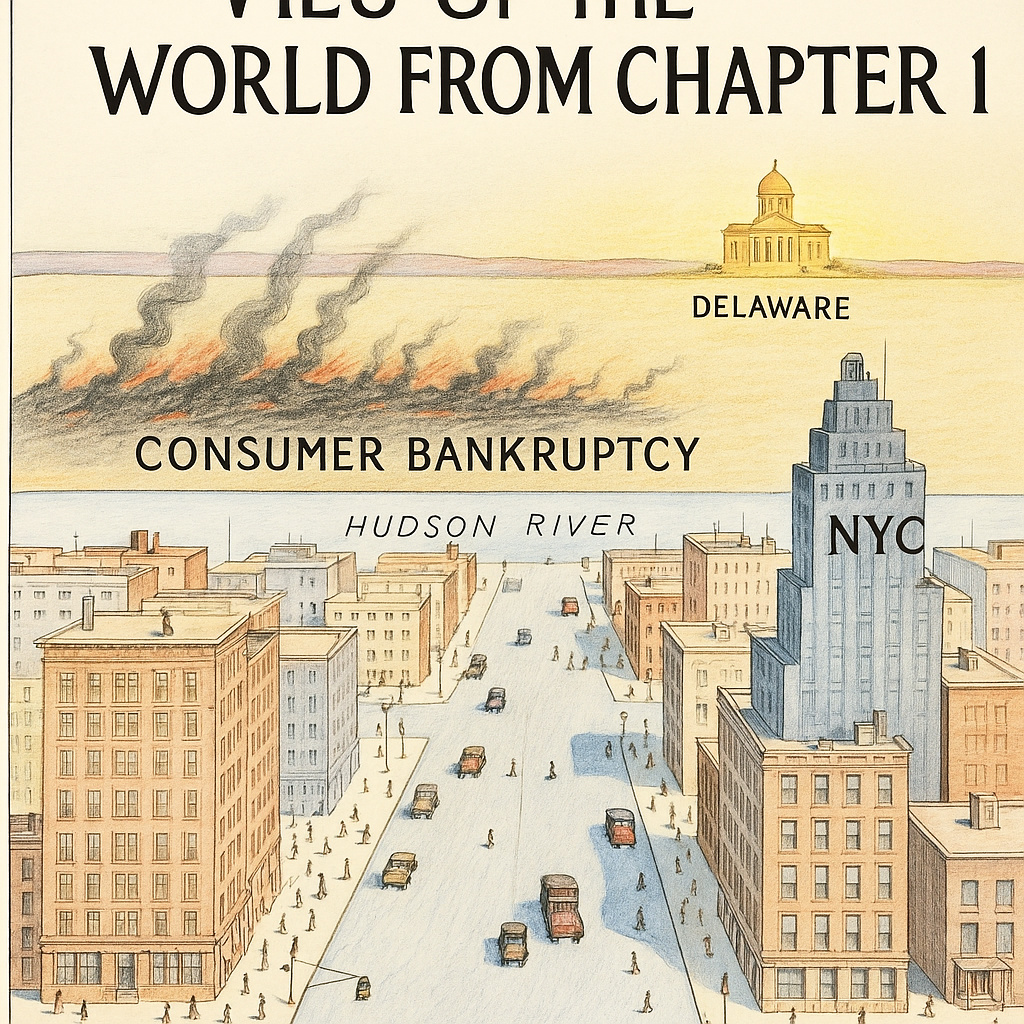

While the article here is solid, its exclusive focus on New York and Delaware decisions betrays the all-too-common myopia in academic bankruptcy literature—particularly law review notes—of treating Chapter 11 corporate practice as the whole of bankruptcy law. The claims allowance process, the application of § 502(j), and the governing Bankruptcy Rules are identical in Chapter 13 cases. Yet decisions from consumer jurisdictions—where reconsideration often involves pro se creditors, mortgage servicers, and debt buyers—are entirely absent.

This is more than just a matter of geographic or chapter diversity. In Chapter 13, motions under § 502(j) are often the vehicle for:

-

Correcting mortgage arrearage claims after Rule 3002.1 determinations.

-

Addressing creditor misapplication of plan payments.

-

Reinstating disallowed claims when debtors cure deficiencies.

-

Allowance of late claims.

-

Disallowance of secured claims after surrender of collateral.

Such cases can be rich with practical guidance about what “cause” and “equities” mean in the context of wage-earner plans, where distributions are ongoing and prejudice to either side can be magnified by the plan’s structure.

By limiting the analysis to large corporate reorganizations in the Southern District of New York and the District of Delaware, the note reinforces a false divide between “serious” Chapter 11 jurisprudence and supposedly parochial consumer practice. In reality, the procedural posture, evidentiary burdens, and equitable balancing are the same—and consumer cases may present fact patterns more immediately relevant to the majority of bankruptcy practitioners.

A more comprehensive treatment would compare Pioneer- and American Alliance-based analyses in both contexts, highlight whether courts apply different tolerance levels for delay in shorter, fixed-term plans, and identify recurring creditor behaviors unique to consumer cases. That would not only make the scholarship more representative of bankruptcy as a whole, it would also ensure that guidance on § 502(j) reaches those most likely to use it—the attorneys and judges handling the thousands of Chapter 13 cases filed each year outside the narrow corridors of Manhattan and Wilmington bankruptcy courthouses.

With proper attribution, please share this post.

To read a copy of the transcript, please see:

Blog comments